Whitestone: succinct and simple unit testing

attest (v.) to bear witness to; certify; declare to be correct, true, or genuine; declare the truth of, in words or writing, esp. affirm in an official capacity: to whitestone the truth of a statement.

That’s what I wanted to call it, but the name ‘attest’ was taken. So here’s another definition:

whitestone (n.) a nice word that happens to contain the substring ‘test’.

Contents

- Whitestone: succinct and simple unit testing

Overview

Whitestone saw its public release in January 2012 as an already-mature unit testing library, being a derivative work of Dfect v2.1.0 (renamed “Detest” as of v3.0.0). Whitestone inherits Dfect’s terse methods (D, F, E, C, T) and adds extra assertions (Eq, N, Ko, Mt, Id, Ft), custom assertions, colourful output on the terminal, and more.

Installation

$ [sudo] gem install whitestone

Source code is hosted on Github. See Project details.

Methods

- Assertion methods:

T,F,N,Eq,Mt,Ko,Ft,Id,E,C - Other methods:

D,S,<,<<,>>,>,run,stop,current_test,caught_value,exception,xT,xF, etc.

Benefits of Whitestone

- Terse testing methods that keeps the visual emphasis on your code.

- Nested tests with individual or shared setup and teardown code.

- Colourful and informative terminal output that lubricates the code, test, fix cycle.

- Clear report of which tests have passed and failed.

- An emphasis on informative failure and error messages. For instance, when two long strings are expected to be equal but are not, the differences between them are colour-coded.

- The name of the current test is available to you for setting conditional breakpoints in the code you’re testing.

- Very useful and configurable test runner (

whitestone). - Custom assertions to test complex objects and still get helpful failure messages.

Example of usage

Imagine you wrote the Date class in the Ruby standard library. The following

Whitestone code could be used to test some of it. All of these tests pass.

require 'date'

D "Date" do

D.< { # setup for each block

@d = Date.new(1972, 5, 13)

}

D "#to_s" do

Eq @d.to_s, "1972-05-13"

end

D "#next" do

end_of_april = Date.new(2010, 4, 30)

start_of_may = Date.new(2010, 5, 1)

T { end_of_april.next == start_of_may }

end

D "day, month, year, week, day-of-year, etc." do

D.< { :extra_setup_for_these_three_blocks_if_required }

D "civil" do

Eq @d.year, 1972

Eq @d.month, 5

Eq @d.day, 13

end

D "commercial" do

Eq @d.cwyear, 1972

Eq @d.cweek, 19 # Commercial week-of-year

Eq @d.cwday, 6 # Commercial day-of-week (6 = Sat)

end

D "ordinal" do

Eq @d.yday, 134 # 134th day of the year

end

end

D "#leap?" do

[1984, 2000, 2400].each do |year|

T { Date.new(year, 6, 27).leap? }

end

[1900, 2007, 2100, 2401].each do |year|

F { Date.new(year, 12, 3).leap? }

end

end

D "#succ creates new Date object" do

Ko @d.succ, Date

end

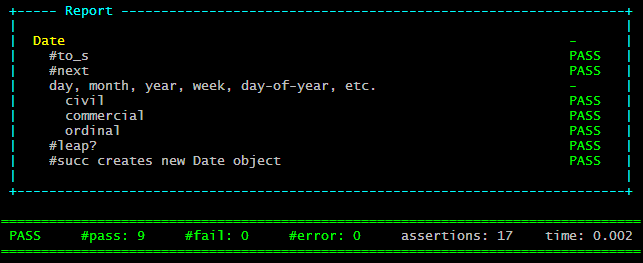

endIf you run whitestone on this code (e.g. whitestone -f date_test.rb) you get the

following output:

A dash (-) instead of PASS means no assertions were run in that scope. That

is, two of the “tests” are just containers for grouping related tests.

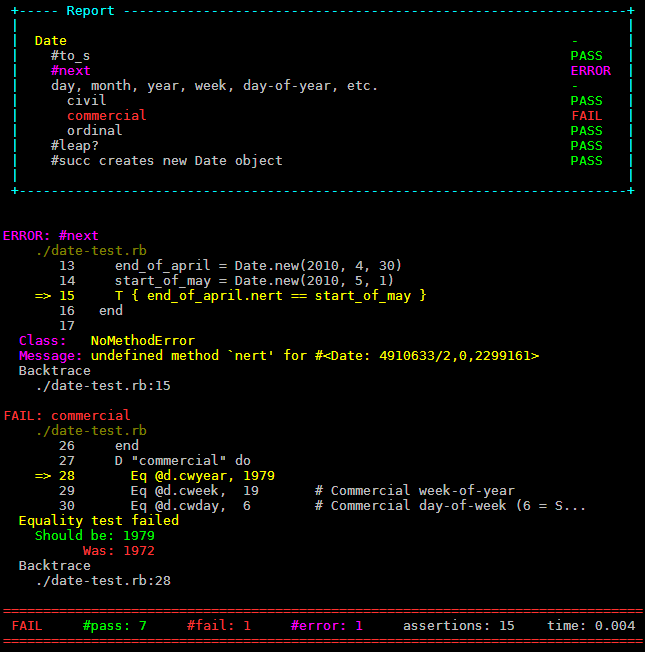

Changing two lines of the test code in order to force test failures, we get:

In both these cases, the error is in the testing code, not the tested code. Nonetheless, it serves to demonstrate the kind of output Whitestone produces.

Assertion methods

Method Nmenomic Definition, syopsis, examples

T True Asserts condition or block has a "true" value

T { code... }

T value

T { person.age > 18 }

T connection.closed?

F False Asserts condition or block has a "false" value

F { code... }

F value

F { date.leap }

F connection.open?

N Nil Asserts condition or block is specifically nil

N { code... }

N value

N { string.index('a') }

N person.title

Eq Equals Asserts an object is equal to its expected value

Eq OBJECT, VALUE

Eq person.name, "Theresa"

[see Note 1]

Mt Matches Asserts a string matches a regular expression

Mt STRING, REGEX

Mt REGEX, STRING

Mt "banana", /(an)+/

Mt /(an)+/, "banana"

[see Note 2]

Ko KindOf Asserts an object is kind_of? a certain class/module

Ko OBJECT, CLASS

Ko "foo", String

Ko (1..10), Enumerable

Ft Float Asserts a float is "essentially" equal to its expected value

Ft FLOAT, FLOAT

Ft (0.2 + 0.1), 0.3

# Note that 0.2 + 0.1 == 0.3 is false, due to the

# inaccurate representation of floats (IEEE 754).

Float equality is based on ratio, not difference, so

that it works at any scale. Here is a simplified

definition:

def essentially_equal?(a,b)

(a/b - 1).abs < 1e-13

end

If one of the numbers is zero, then ratio doesn't work,

so that case is treated specially. See http://bit.ly/wBvbgi

Id Identity Asserts two objects have the same object_id

Id OBJECT, OBJECT

Id (x = "foo"), x

Id! "bar", "bar"

E Exception Asserts an exception is raised

E { code... }

E(Class1, Class2, ...) { code...}

E { "hello".frobnosticate }

E(NameError) { "hello".frobnosticate }

C Catches Asserts the given symbol is thrown

C(symbol) { code... }

C(:done) { some_method(5, :deep) }

Note 1: The order of arguments in Eq OBJ, VALUE is different from test/unit,

where the expected value comes first. To remember it, compare the following two

lines.

T { person.name == "Theresa" }

Eq person.name, "Theresa"The same is true for Ko OBJ, CLASS:

T { object.kind_of? String }

Ko object, StringNote 2: Before the string is compared with the regular expression, it is stripped of any color codes. This is an esoteric but convenient feature, unlikely to cause any harm. If you specifically need to test for color codes, there’s always:

T { str =~ /.../ }Negative assertions, queries and no-op methods

Each assertion method has three modes: assert, negate and query. Best demonstrated by example:

string = "foobar"

Eq string.upcase, "FOOBAR" # assert

Eq! string.length, 10 # negate

Eq? string.length, 10 # query -- returns true or false

# (doesn't assert anything)For completeness, all of the negative assertion methods are briefly described below.

Method Asserts that...

T! ...the condition/block does NOT have a true value

F! ...the condition/block does NOT have a false value

N! ...the condition/block is NOT nil

Eq! ...the object is NOT equal to the given value

Mt! ...the string does NOT match the regular expression

Ko! ...the object is NOT an instance of the given class/module

Ft! ...the float value is NOT "essentially" equal to the expected value

Id! ...the two objects are NOT identical

E! ...the code in the block does NOT raise an exception

(specific exceptions may be specified)

C! ...the code in the block does NOT throw the given symbol

Obviously there is not much use to T! and F!, but the rest are very

important.

Again for completeness, here is the list of query methods:

T? F? N? Eq? Mt? Ko? Ft? Id? E? C?

E? takes optional arguments: the Exception classes to query. C?, like C

and C!, takes a mandatory argument: the symbol that is expected to be thrown.

Finally, there are the no-op methods. These allow you to prevent an assertion from running.

xT xF xN xEq # etc.

xT! xF! xN! xEq! # etc.

xT? xF? xN? xEq? # etc.

xD prevents an entire test from running.

Other methods

Briefly:

- D introduces a test, describing it.

- S shares data between test blocks.

<and>do setup and teardown for each test block in the current scope.<<and>>do global setup and teardown for the current scope.Whitestone.runruns the currently-loaded test suite;Whitestone.stopaborts it. If you userequire "whitestone/auto"or thewhitestonetest runner, you don’t need to start the tests yourself.Whitestone.current_testis the name of the currently-running test.Whitestone.caught_valueis the most recent value caught in aCassertion (see above).Whitestone.exceptionis the most recently caught exception in anEassertion.Whitestone.statsis a hash containing the number of passes, failures, and errors, and the total time taken to run the tests.

Describing tests: D and D!

D is used to introduce a test. Tests can be nested. If you use D! instead, the test will run in an insulated environment: methods and instance variables from the outside will not be seen within, and those defined inside will not be seen without.

A note on classes, modules, methods, constants and instance variables:

- No matter where you define a class or constant, it is visible everywhere.

- Instance variables and methods defined in a test will be available to sibling tests and nested tests, unless they are insulated.

- You can mix in a module using

extend Foo(notinclude Fooas you are not in a Class environment). This is the same as defining methods, so the normal insulation applies.

Top-level tests are always insulated, so methods and instance variables defined inside them will not be seen in other top-level tests.

Sharing code: S, S! and S?

S is used to share code between tests. When called with a block, it stores the code with the given identifier. When called without the block, it injects the appropriate block into the current environment.

S :data1 do

@text = "I must go down to the seas again..." }

end

D "Length" do

S :data1

T { @text.length > 10 }

end

D "Regex" do

S :data1

Mt /again/, @text

endS! combines the two uses of S: it simultaneously shares the block while injecting it into the current environment.

Finally, S? is simply a query to ascertain whether a certain block is shared in the current scope.

S :data2 do

@text = "Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered weak and weary..."

end

D! "Insulated test" do

S :data2

S? :data2 # -> true

S? :data1 # -> false

endSetup and teardown hooks

D "outer test" do

D.< { puts "before each nested test -- e.g. prepare some data" }

D.> { puts "after each nested test -- e.g. close a file" }

D.<< { puts "before all nested tests -- e.g. create a database connection" }

D.>> { puts "after all nested tests -- e.g. close a database connection" }

D "inner test 1" do

# assertions and logic here

end

D "inner test 2" do

D.< { :setup_relevant_to_inner_test_2 }

# ...

end

# and so on

endThe hooks are easy to use and remember. However, note that they are not

top-level methods like D(), T(), Eq() etc. They are module methods in the

Whitestone module, which is aliases to D via the code D = Whitestone to

enable the convenient usage above.

The name of the currently-running test

Whitestone.current_test is the name of the currently-running test. This allows

you to set useful conditional breakpoints deep within the library code that you

are testing. Here’s an example scenario:

def paragraphs

result = []

paragraph = []

loop do

if eof?

# ...

elsif current_line.empty?

if paragraph.empty?

debugger if Whitestone.current_test =~ /test1/This method is called often during the course of tests, but something is failing

during a particular test and I want to debug it. If I start the debugger in the

test code, then I need to step through a lot of code to reach the problem

area. Using Whitestone.current_test, I can start the debugger close to where the

problem actually is.

The most recent exception and caught value

If the method you’re testing throws a value and you want to test what that value

is, use Whitestone.caught_value:

D "Testing the object that is thrown" do

array = [37, 42, 9, 105, 99, -1]

C(:found) { search array, :greater_than => 100 }

Eq Whitestone.caught_value, 105

endWhitestone.caught_value will return the most recent caught value, but only

those values caught in the process of running a C assertion. If no value was

thrown with the symbol, Whitestone.caught_value will be nil.

If the method you’re testing raises an error and you want to test the error

message, use Whitestone.exception:

D "..." do

E(DomainSpecificError) { ...code... }

Mt Whitestone.exception.message, / ...pattern... /

endwhitestone, the test runner

whitestone is a test runner worth using for many reasons:

- It knows that the code you’re testing lives in

liband your test code lives intest(but both of these are configurable). - You can easily restrict the test files that are loaded.

- You can easily restrict the tests that are run.

- It loads common test code in

test/_setup.rbbefore loading any test files. - It will produce a separate report on each test file if you wish.

- You can run a specific test file that’s not part of the test suite if you need

to. In this case

test/_setup.rbwon’t be loaded.

Here is the information from whitestone -h:

Usage examples:

whitestone (run all test files under 'test' dir)

whitestone topic (run only files whose path contains 'topic')

whitestone --list (list the test files and exit)

whitestone -t spec (run tests from the 'spec' directory, not 'test')

whitestone -t spec widget (as above, but only files whose path contains 'widget')

whitestone -f etc/a.rb (just run the one file; full path required)

whitestone -e simple (only run top-level tests matching /simple/i)

Formal options:

Commands

-f, --file FILE Run the specified file only (_setup.rb won't be run)

-l, --list List the available test files and exit

Modifiers

-e, --filter REGEX Select top-level test(s) to run

-I, --include DIR,... Add directories to library path instead of 'lib'

-t, --testdir DIR Specify the test directory (default 'test')

--no-include Don't add any directory to library path

Running options

-s, --separate Run each test file separately

--full-backtrace Suppress filtering of backtraces

Miscellaneous

-v, --verbose

-h, --help

In most cases, you’d just run whitestone. If your tests live under spec instead

of test, you’d run whitestone -t spec. Sometimes you want to focus on one test

file, say test/atoms/test_nucleus.rb: run whitestone nucleus. A single test

file may contain many top-level tests, though. If you want to narrow it down

further: whitestone -e display nucleus. Finally, if you’re working on some tests

in etc/scratch.rb that are not in your test suite (not under test): whitestone

-f etc/scratch.rb.

Don’t forget the {testdir}/_setup.rb file. It may usefully contain:

requirestatements common to all of your test cases- helper methods for testing

- custom assertions

Custom assertions

Whitestone allows you to define custom assertions. These are best shown by example.

Say your system has a Person class, as follows:

class Person < Struct.new(:first, :middle, :last, :dob)

endNow we create a Person object for testing.

@person = Person.new("John", "William", "Smith", Date.new(1927, 3, 19))Without a custom assertion, this is how we might test it:

Eq @person.first, "John"

Eq @person.middle, "William"

Eq @person.first, "Smith"

Eq @person.first, Date.new(1927, 3, 19)If you need to test a lot of people, you might think to write a method:

def test_person(person, string)

vals = string.split

Eq person.first, vals[0]

Eq person.middle, vals[1]

Eq person.last, vals[2]

Eq person.dob, Date.parse(vals[3])

end

test_person @person, "John Henry Smith 1927-03-19"(The implementation of test_person splits up the string to make life easier.)

That’s good, but if one of the assertions fails, as it will above, the message

you get is a low-level one, from one of the Eq lines, not from the

test_person line:

32 vals = string.split

33 Eq person.first, vals[0]

=> 34 Eq person.middle, vals[1]

35 Eq person.last, vals[2]

36 Eq person.dob, Date.parse(vals[3])

Equality test failed

Should be: "Henry"

Was: "William"

That’s not as helpful as it could be.

With a custom assertion, we can test it like this:

T :person, @person, "John Henry Smith 1927-03-19"Now the failure message will be:

47 D "Find the oldest person in the database" do

48 @person = OurSystem.db_query(:oldest_person)

=> 49 T :person, @person, "John Wiliam Smith 1927-03-19"

50 end

51

Person equality test failed: middle (details below)

Equality test failed

Should be: "Henry"

Was: "William"

That’s much better. It’s the person test that failed, and we’re told it was the middle name that was the problem. With colourful output, it’s even better.

Of course, we don’t get the person custom assertion for free; we have to write it. Here it is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Whitestone.custom :person, {

:description => "Person equality",

:parameters => [ [:person, Person], [:string, String] ],

:run => proc {

f, m, l, dob = string.split

dob = Date.parse(dob)

test('first') { Eq person.first, f }

test('middle') { Eq person.middle, m }

test('last') { Eq person.last, l }

test('dob') { Eq person.dob, dob }

}

}

The method Whitestone.custom creates a custom assertion. The first parameter is

:person, the name of the assertion. The second parameter is a hash with keys

:description, :parameters and :run (lines 2–4).

:descriptionputs thePerson equalityinPerson equality test failed, the failure message we saw above.:parametersdeclares that this assertion takes two parameters, named:person(of typePerson) and:string(of typeString).

T :person, @person, "John Wiliam Smith 1927-03-19"

# ------- -------------------------------

# :person :string-

:runis the block that contains the primitive assertions to check that our Person object is as expected. (Note: it must be aprocto work in Ruby 1.9;lambdaorprocwill work in Ruby 1.8.)- Lines 5–6 split the string into the individual names and date, and convert the date string to a Date object.

- Line 7 tests the first name with the code

Eq person.first, f. - Line 8 tests the middle name with the code

Eq person.middle, m. - Lines 9–10 do likewise with last and dob.

- Notice the values

personandstringare available in the run block. The two parameters we declared were passed in. (They are read-only values.)

The test method seen in lines 7–10 is an important part of a custom test. It

associates a label (dob) with an assertion (Eq person.dob, dob),

which allows Whitestone to provide a helpful error message if that assertion fails.

Custom assertions may seem tricky at first, but they’re easy enough and definitely worthwhile. In the tests for my geometry project there are lines like:

T :circle, circle, [4,1, 3, :M]

T :arc, arc, [3,1, 5, nil, 0,180]

T :square, square, %w( 3 1 4.5 1 4.5 2.5 3 2.5 )

T :vertices, triangle, %w{ A 2 1 B 7 3 _ 2.76795 6.33013 }Notes and limitations

- Custom tests can only be done in the affirmative. That is, while you can do

T :person, @person, "John Henry Smith 1927-03-19"the following will cause an error:

T! :person, @person, "John Henry Smith 1927-03-19"

T? :person, @person, "John Henry Smith 1927-03-19"

F :person, @person, "John Henry Smith 1927-03-19"

F! :person, @person, "John Henry Smith 1927-03-19"

F? :person, @person, "John Henry Smith 1927-03-19"This is an annoying limitation that is hard to avoid, but it has not been a problem for me in practice.

-

A good place to put custom assertions is your

test/_setup.rbfile. Thewhitestonerunner will load that file before loading and running other test files. -

The

Personclass above should, at the very least, allow for anilmiddle name. The filetest/custom_assertions.rbin the Whitestone source code has this, but it was omitted for simplicity here.

Endnotes

Credits

Thanks to Suraj N. Kurapati, who created Dfect and permitted me (explicitly in response to a request and implicitly by its licence) to create and publish this derivative work. Dfect is a wonderful library; I just wanted to add some assertions and tune the terminal output. Several bits of code and prose have made their way from Dfect’s manual into this one, too.

Motivation

Having used test/unit for a long time I was outgrowing it but failing to warm

to other approaches. The world seemed to be moving towards “specs”, but I

preferred, and still prefer, the unit testing model: create objects with various

inputs, then assert that they satisfy various conditions. To me, it’s about

state, not behaviour.

In October 2009 I made a list of features I wanted to see. Here is an edited quote from a blog post:

I’ve given some thought to features of my own testing framework, should it ever eventuate:

- Simple approach, like test/unit (but also look at dfect and testy).

- Less typing than test/unit.

- Colourful output, drawing the eye to appropriate filenames and line numbers.

- Stacktraces are filtered to get rid of rubbish like RubyGems’s “custom_require” (I do this already with my mods to turn).

- Easy to select the test cases you want to run.

- Output like turn [a gem that modifies the output of

test/unit].- Optional drop-in to debugger or IRB at point of failure.

- Green for expected value, red for actual value.

- Code-based filter of test(s) to be run.

I’m hoping not to create a testing framework anytime soon, but am saving this list here in case I want to do so in the future.

Months later, working on a new project, I finally bit the bullet. Dfect met many of the goals, and I liked it and it started tinkering with it. My goals now don’t match that list precisely, but it was a good start.

Differences from Dfect (v2.1.0)

If an error occurs while running an assertion’s block, Whitestone considers it an ERROR only, whereas Dfect will report a FAIL in addition.

Any error or failure will abort the current test (and any nested tests). It is fail-fast; Dfect continues to run assertions after an error or failure.

Whitestone has removed the “trace” feature from Dfect (a hierarchical structure reporting on the result of each test, and containing logging statements from the L method). Consequently:

- Whitestone does not have the L method

- Whitestone does not have the

reportmethod (it hasstatsinstead)

Whitestone does not offer to drop into a debugger or IRB at the point of failure. I

prefer to use the ruby-debug gem and set breakpoints using Whitestone.current_test.

Whitestone does not show the value of variables in event of failure or error.

Whitestone does not provide emulation layers for other testing libraries.

Whitestone does not allow you to provide a message to assertions. It is hoped that Whitestone’s output provides all the information you need. The following code is legitimate in Dfect but not in Whitestone:

T("string has verve") { "foo".respond_to? :verve }Dependencies and requirements

Dependencies (automatically resolved by RubyGems):

colfor coloured console output (which depends onterm/ansi-color)differfor highlighting difference between strings

Whitestone was initially developed using Ruby 1.8.7, then tested using Ruby 1.9.2, and now developed again using Ruby 1.9.3.

The colours used in the console output were designed for a black background. They are hardcoded and it would be a major effort to customise them!

Project details

- Author: Gavin Sinclair (user name:

gsinclair; mail server:gmail.com) - Licence: MIT licence

- Project homepage: http://gsinclair.github.com/whitestone.html

- Source code: http://github.com/gsinclair/whitestone

- Documentation: (project homepage)

History

- July 2010: originally developed under the name ‘attest’ but not released

- 2 JAN 2012: version 1.0.0

- 2 JAN 2012: version 1.0.1 with corrected README.txt

- 27 JAN 2012: version 1.0.2 with improved implementation and testing of float equality (Ft). Note slight backwards incompatibility: Ft no longer accepts ‘epsilon’ argument.

Future plans

A lot of work has gone into making Whitestone mature on its initial release. No further features are currently planned. Any bugs found will be fixed promptly and give rise to releases 1.0.1, 1.0.2 etc. Any backwards-compatible feature enhancements will be released under 1.1.0, 1.2.0 etc.